Nested Functions and Closures

Consider this ChocoPy program:

def f(x : int) -> int:

def g(y : int) -> int:

return x + y

return g(10) + g(7)

print(f(6))

It prints 29. The function g has its definition nested within the body

of f, and it has access to read the parameter x of the f function.

How might we compile this?

If we were compiling to traditional assembly, we could have the stack frame

for g refer to the stack frame for f, since all stack memory in a

traditional process is part of the same address space. We could compile g

to do a specific memory-offset lookup for x in order to find it in its

caller’s frame, which is reminiscent the infrastructure for getting the

address of variables in C/C++ (the & operator).

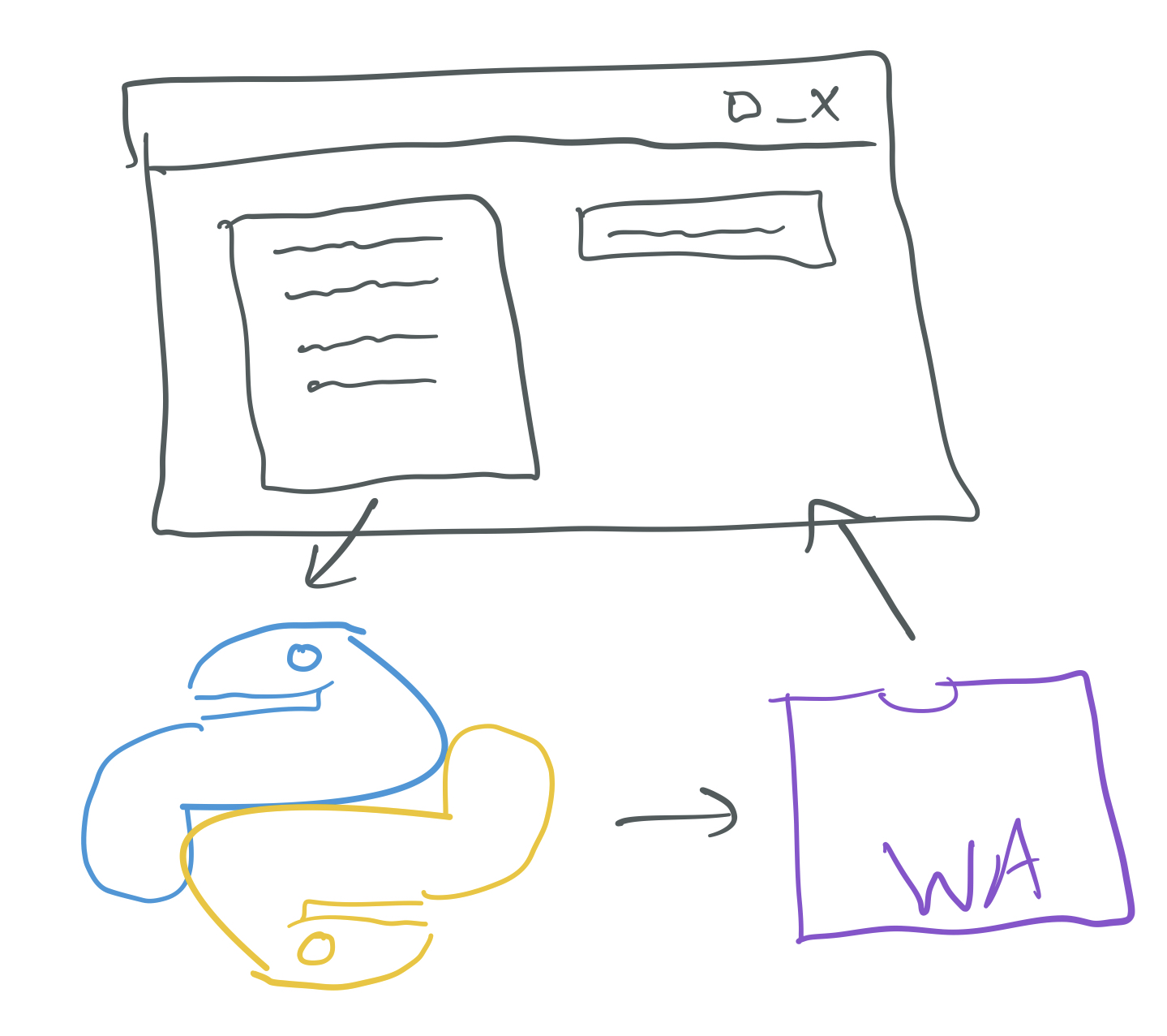

In WASM, we cannot do this! Since WASM doesn’t permit access to the stack

outside of the current function, such a cross-call variable reference is

prohibited. We need another strategy to implement nested functions atop WASM.

Our approach to this could be multi-faceted, depending on the particular

constraints of g and f.

Inlining

One straightforward option, if g is not recursive, and not too large, and

not used too many times, is inlining. In many programs, nested functions are

small helpers, and their code can be easily copied to the point where they

are called. In this case, that would mean replacing the expressions g(10)

with x + 10, and g(7) with x + 7.

Inlining is an implementation technique that we can perform at the source level by transforming the AST directly, and the updated AST would then have WASM code generated for it as usual. However, due to recursion, it is not a general solution, and due to code size concerns, it is not a pragmatic solution for all cases.

Adding Extra Arguments to g

For nested functions with ChocoPy’s restrictions (we’ll revisit this

restriction later), we know that all calls to g must occur within the body

of f. Generally, all calls to a nested function appear within the body of

the function it is declared in. This gives us some constraints that allow us

more freedom with compilation than we have with other functions. In

particular, we know g cannot be exported and called from another REPL

entry, so if we wanted to, say, change its signature to add or remove

arguments, we could also find all of the places that call g and update them

appropriately.

A concrete proposal for handling nested functions is to find all of the variables that the function uses that aren’t defined within the function (and aren’t global), and add them as extra arguments. Then at the call sites, we can pass in the appropriate values. This has a nice side effect – we can move these programs to the toplevel, because they no longer refer to any variables that aren’t global or their own parameters! This immediately gives us a compilation strategy for them (with a little work on naming).

In this proposal, we would have our compiler transform this program into:

# We use the name f_g to indicate that this was the g we pulled out of f

# In WASM generation we'd use f$g, I use the underscore to keep these

# runnable in Python

def f_g(x: int, y : int) -> int:

return x + y

def f(x : int) -> int:

return f_g(x, 10) + f_g(x, 7)

print(f(6))

This requires implementing a new algorithm in our compiler that calculates the set of nonlocal variables in a function definition. The calculation of this set of variables is similar to the kinds of calculations we have to do to build environments for our functions or look for undefined identifiers, but with the goal of finding names that need this extra-argument treatment.

Unfortunately, this transformation is brittle in the presence of other

features, even within the restrictions of ChocoPy. ChocoPy allows for the

nonlocal Python keyword, which makes it so a nested function can perform

updates to a variable from outside its scope. Consider this example:

def f(x : int) -> int:

def g(y : int) -> int:

return h(y) + x

def h(z : int) -> int:

nonlocal x

x = z

return x + 1

return g(10) + g(7)

print(f(6))

This program prints 36 when run through ChocoPy. Crucially, by the time we

look up the value of x in g, it is always updated to be the same as the

value of y. So the first call to g returns 21 (11 + 10), and the second

returns (8 + 7). But consider applying the transformation we suggested in the

last step:

def f_g(x : int, y : int) -> int:

return f_h(x, y) + x

def f_h(x : int, z : int) -> int:

nonlocal x # unclear what this line means anymore since x is local

x = z

return x + 1

def f(x : int) -> int:

return f_g(x, 10) + f_g(x, 7)

print(f(6))

In both Python and ChocoPy, this program produces a static error that x is

defined twice. Aside from this complication, g has its own x parameter,

which is unaffected by modifications to x in other places. So if we drop

the nonlocal line to get rid of the “error”, this program produces a

different answer (31 instead of 36).

And in fact, Python with nonlocal declarations is closer to the

interesting-case behavior of most programming languages – multiple functions

can perform updates on, and see the value of, a shared variable.

So adding an extra parameter works, but not if we want to support use cases that share updateable variables between functions.

Storing Shared Variables on the Heap

Another attempt could be to store, update, and access shared variables on the

heap (in WASM, the linear memory). This is promising, because the memory

persists across all function calls, and indeed, in our setup, across other

boundaries like modules. Our approach will be to give special treatment and

attention to variables that both updated at some point, and used within

a nested function, like x in our f-g-h example above. We will call these

variables nonlocally-mutable variables.

For this development, let’s imagine that there exists a class Ref that’s

globally available in our Python implementation, that has a single field:

class Ref:

value: int = 0

We will take the approach of adding extra arguments for free variables as

before, but with a key modifications. For each nonlocally-mutable

variable x, we:

- Change its definition to be of type

Refinstead ofint, and its initial value to be a newly-createdRefobject with the initial value in thevaluefield - Change all uses of the variable to

x.value, except when passingxas an extra argument - Change all variable updates to the variable from

x = etox.value = e

This would rewrite our program from above as:

def f_g(x : Ref, y : int) -> int:

return f_h(x, y) + x.value

def f_h(x : Ref, z : int) -> int:

x.value = z

return x.value + 1

def f(x_1 : int) -> int:

x : Ref = None

x = Ref()

x.value = x_1

return f_g(x, 10) + f_g(x, 7)

print(f(6))

We also changed the original name x (a paramter of f) to be x_1, so

that we could redefine x correctly in the body of f. This program, when

run in ChocoPy or Python, produces the expected answer of 36. If we trace

through the evaluation of this program, we see the shared behavior emerges.

When we evaluate x = Ref(), we create the single shared location on the

heap for this x variable. Then that object reference is passed through

f_g and f_h, which can see and update that same shared location through

x.value. The uses of x.value then observe that shared location at the

correct times and see the values we expect from the original program.

Gradually Increasing Complexity

All three of these strategies—inlining, adding extra arguments, and creating references for variables variables—are useful. Inlining can actually reduce the number of instructions run by a program. Adding extra arguments causes more work (extra pushing of arguments) in exchange for working on recursive functions and functions that might be too costly to inline. Creating references for variables makes yet more work at runtime, in the form of allocations and memory access, which is less efficient than stack access alone.

Here we have a classic case in compiler design – for different kinds of complexity in a program, we can use different compilation techniques to compile the “same” programming language feature (in this case nested functions). Another view is that adding references around variables always works as a fully general solution, but if the variable is never updated it’s safe to remove the references as an optimization, and if the function is sufficiently small, we could inline instead.

An optimizing compiler for Python ought to do the analysis described above, and choose which one of the compilation strategies to use based on the complexity of the nested functions. The questions of when to inline, and in how many cases we can avoid wrapping variables in references, become new, fruitful areas of measurement and exploration for the compiler author. On a large compiler team, a single developer’s entire job might be to test out different heuristics that work well for deciding which functions to inline! In this example we begin to see the true sophistication that goes into modern compiler design.

def f(x : int) -> int:

def g(y : int) -> int:

if y > 10:

return h(y + n)

else:

return x

def h(z : int) -> int:

n : int = 0

n = 100 + z

return x + n

n : int = 0

n = 500

return g(15) + g(7)

print(f(6))