Classes and Inheritance

In lecture 8 we saw a simple implementation of classes-as-structs. The main components of the implementation were:

- Adding

classdefinitions to the AST - Managing the heap offset (stored in the first word of the heap) through a mix of program analysis (counting globals) and dynamic updates (when constructing an object)

- Changing the AST to be decorated with types so we could carry type information through to the compiler

This was completely sufficient infrastructure for implementing object construction and field access. We left the (I claim trivial) additions of field update and initialization as exercises to the reader.

We left un-implemented methods and any mention of inheritance. It turns out that these concepts are quite interesting and provide a useful introduction to more sophisticated uses of functions, so we will discuss them here.

Methods Without Inheritance

First, we can consider methods without any mention of inheritance. In one

of the examples from week

4, there

is an inc method:

class Counter(object):

n : int = 0

def inc(self : Counter):

self.n = self.n + 1

c : Counter = None

c = Counter()

c.inc()

print(c.n)

c.inc()

print(c.n)

In the case of no inheritance, where we have our decorated AST, let’s

consider the c.inc() expressions in this program.

The self Argument

An important Python/ChocoPy semantic note is in order: the self argument is

explicit in the method definition, so it looks like the method takes one

more argument than is provided at the call site. We will (for now) think of

c.inc() as a call to a function Counter_inc that provides the value of

c as an argument.

c.inc() → Counter_inc(c)

This is another case where we need the class of the object in order to compile it!

Generating Code for Method Calls

We’d need a new AST form for method calls, probably something like:

| { a?: A, tag: "methodcall", obj: Expr, name: string, args: Array<Expr> }

To type-check this expression, we’d need to do similar work to field lookup combined with function calls:

- Calculate the type of

obj, and extract the class name - Look up the type of that method in the environment (note we’re assuming an augmented class environment with method types along with the field types we showed in lecture)

- Calculate the types of the arguments

- Compare the arguments to the parameter types of the method

- Produce the calculated type of the return type of the method

Running the type-checker would leave us with an expression decorated with the

return type (in this case <none>), and with the obj field decorated with

the object’s class type. The latter is important for later compilation.

In order to generate code for the decorated expression, we’d need to

- Get generated code for the object position

- Get generated code for each of the arguments

- Use the decorated class name on

obj, along with the name of the method, to create the method nameCounter_inc - Create a

callinstruction toCounter_inc

Note that the generated code for the object position puts it as the first

argument on the stack for Counter_inc.

Other Details

The strategy above implies a few design decisions:

- For each class, we will generate a sequence of function definitions that combine the class name with the function name, corresponding to the method definitions.

- There’s a small detail we’d need to get right here – we need to make sure

if a user writes a function called

Counter_incthemselves, it won’t cause an error for in the generated code for both functions being defined! We can get around this by adding a character that is allowed in WASM names but not in Python names, like$. So we might name the function from the classCounter$incinstead. - We need to augment the AST and various environments in a few ways to include information about methods. The method environment in the type checker could store information about the parameter types and return type for each method.

Things to think about:

- What are some new type errors that could occur?

- Are there any new runtime errors that could occur?

- What effects does this have on the REPL?

- what effects does this have on the heap layout (if any)

Adding Inheritance

Without inheritance, classes are glorified structs. We could write all of the

methods as functions, and pass all of the self parameters ourselves, and

our programs would not change in any meaningful way. However, in general

Python and ChocoPy, we can also use inheritance, where we specify a

superclass other than object when defining a class. This forces us to

confront the soul of object-oriented programming: dynamic dispatch.

Consider this program that represents a list:

class List(object):

def sum(self : List) -> int:

return 1 / 0 # Intentional error! Make sure we implement in subclasses

class Empty(List):

def sum(self : List) -> int:

return 0

class Link(List):

val : int = 0

next : List = None

def sum(self : Link) -> int:

return self.val + self.next.sum()

def new(self : Link, val : int, next : List) -> Link:

self.val = val

self.next = next

return self

l : List = None

l = Link().new(5, Link().new(1, Empty()))

print(l.sum())

Focusing on the l.sum() call here, note a few things:

- The type of

lisList, notLink. - The program must somehow compile

l.sum()to call thesummethod in theLinkclass. - The type of

self.nextisList, notLink. - The

self.next.sum()call within theLink.summethod sometimes callsLink.sumand sometimes callsEmpty.sum.

This makes for an interesting challenge for us in compiling method calls in the presence of inheritance:

A single call expression in the source program may select from one of several method definitions at runtime.

This is the essence of dynamic dispatch. It is now our task to figure out how to represent this in our compiler and at runtime.

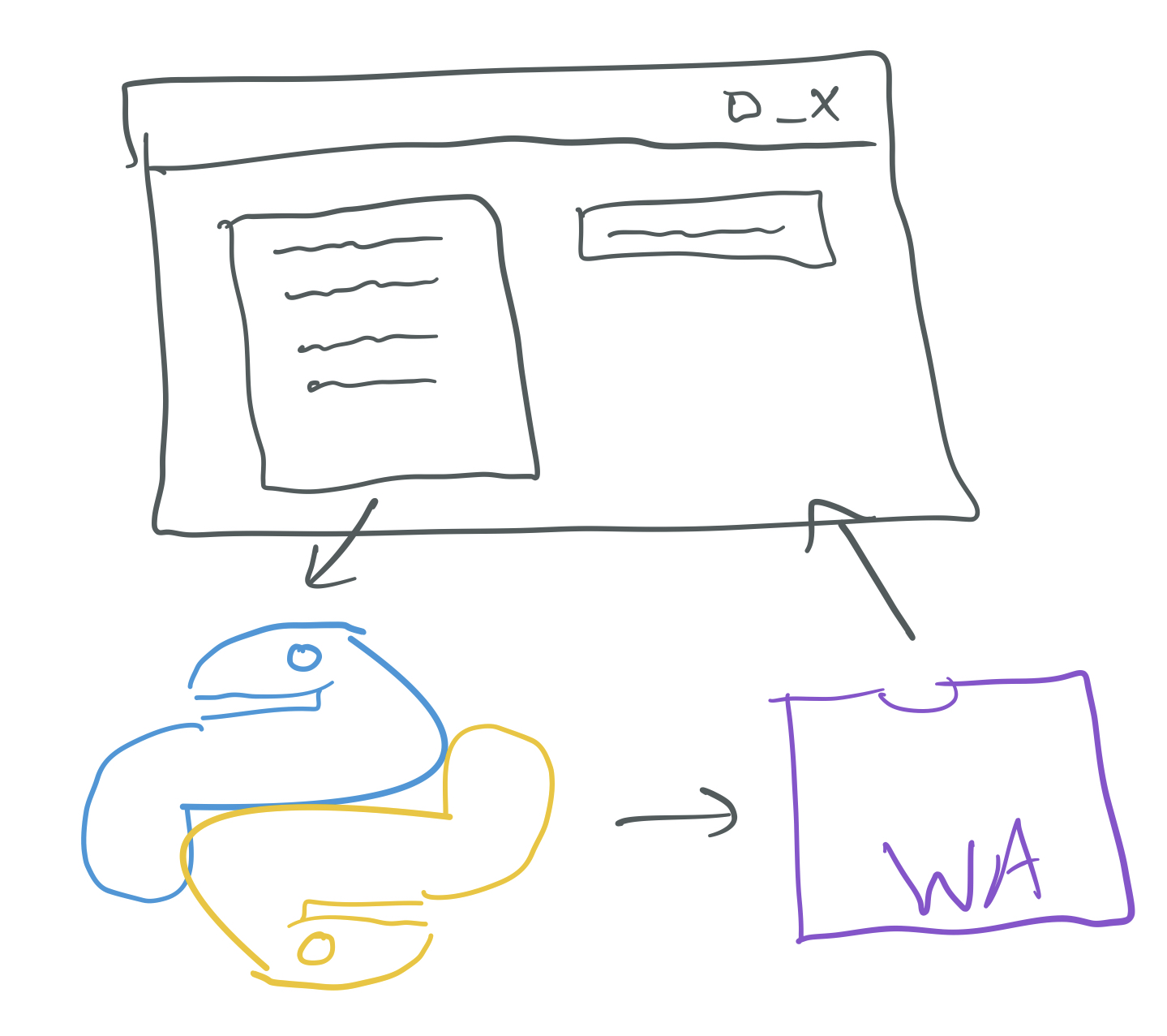

Functions as Values (in WASM, Function References and Tables)

A key consequence of dynamic dispatch is that object values must contain information about their class, because the class of an object cannot be determined statically.

Another consequence is that we need the ability to, at runtime, get references to the appropriate methods based on this stored class information. There are several ways we could accomplish this, we will use a tool and strategy that is standard in WASM for this use case.

The WASM tool is tables and the call_indirect

instruction,

which allow us to refer to a function by a numeric (i32) index into a table

rather than by a name that needs to be known at compile-time. WASM currently

supports a single table per module, so we will need to organize all method

references within the same module-level table.

The strategy we will use in our compiler is to update our representation of objects on the heap to contain extra information about where the methods are located within the current module’s table. Here we have some choice:

- We could add an additional

i32field on each object that represents a starting index into the table where the methods for the class are stored. - We could add an additional

i32field per method, per object, that is a direct index to the location the method is stored within the table.

What are the tradeoffs between these two options?

Let’s assume we choose the first option, and consider the code we might

generate for a method call like l.sum().

;; assume the stack contains the address of the object stored in `l`, and it's

;; a `Link` object

(i32.load) ;; This loads the value of the first i32 word in the object,

;; which in this scheme is a small integer table index to the start

;; of the Link method references in the module's table

(i32.add 0) ;; Let's assume that `sum` is the first method in the list for Link,

;; so its function reference is right at the beginning

;; Note that we have to decide on adding 0 based *just* on knowing

;; that this is a List, statically we don't know that this is a Link

(i32.load <address-of-l-again>) ;; self argument

(call_indirect (type $return_i32))

;; assume $return_i32 is defined as in the docs linked above

;; this will call the function referenced at the index calculated

;; via load and adding the offset for the particular method

In this case, we’d assume a memory layout like:

l val next

| | |

v v v

[ ... | ? | 55 | <address> | ... ]

The ? must hold the location of the methods for the Link class. So a

crucial decision is how we put the method references in the table. A layout

like this might make sense for these classes:

0: List$sum

1: Empty$sum

2: Link$sum

3: Link$new

That is, the classes appear in order as they are declared in the file. A

critical decision we had to make for Link is making sure that sum came

before new, because any List-typed object that is used to call sum

needs to use the same index for that method. So the ? in the memory layout

above ought to be 2 for this example.

This puts a new demand on our compiler – some time before generating code, we need to build the mapping from each class to a starting index and from each class-method pair to an offset. This will allow us to create this table and reference it correctly from generated code.

Questions for discussion:

- What would change in the example above if the method call was to

newinstead ofsum? (Hint: would it be in what’s stored in memory? What’s stored in the table? What’s in the generated code?) - What constraints are important in table layout if there are multiple overridden methods in the superclass and subclasses?

- What should the table look like if a method isn’t overridden by a subclass?

- Which expression or statement’s generated code is responsible for putting

the

2into memory in the example above? What information does code generation need in order to do this?

Supporting a REPL

So far, we’ve had to keep track of several pieces of information to support our REPL:

- The location of each global variable

- The location of a heap offset

- Any defined functions (which we could provide to the REPL with

import) - The types of functions and globals (to support type-checking across REPL entries)

Adding inheritance now means that we need to track the table layout of the class environment across REPL entries as well, and each new REPL module needs access to a running table of function references. Aside from modifying the REPL/runner to consume and produce this new information there’s no new infrastructure required. However, it’s worth pointing out a few things.

First, new classes could be defined at the REPL. To keep things tidy, their method references need to go at higher indices in the table than those from the main module, since any code generated from the main module needs to rely on those fixed references, and any uses of the classes from the main module in the REPL need to keep consistent addresses.

In addition, new classes could be defined at the REPL that contain references to existing classes as superclasses. This means we need to look up information about classes from the environment that may not be defined in the current module, including their types and table layout, and use it to decide on the table layout for new classes.

These use cases help us understand some of the necessary information we need to track across REPL entries, and for separate compilation of programs that use classes in general.